by Erika O'Brien

It is one of those complex and agonising questions that keeps you awake at night…‘Should we tell our child about his/her diagnosis?’. Should you decide, ‘yes’, then the issues of ‘when’ and ‘how’ have to be tackled.

These questions plagued my husband and I for years. We were afraid of the impact that the knowledge of his condition might have on him. We didn’t want our child to have a label which put him in a box and made him feel that he had limited potential. Overwhelmingly, however, the professionals and other experienced parents were expressing the view that the diagnosis did need to be shared, but carefully and at the right time. We wanted to present the information to our son like a thoughtfully chosen, carefully wrapped gift, at the perfect time.

So began our search for the best possible way to present to our son this ‘gift’ of knowledge about himself - one which would help him understand and accept himself, and help him to find the best strategies to cope with any challenges. One idea I really liked was the idea of using the child’s special interest to describe the condition of ASD. Our son likes animals, so there was the idea of showing him different types of big cats…cheetahs, leopards, jaguars, lions and so on. We could explain that they are all cats, but that they have differences on the outside and differences in behaviours and characteristics, as it is with humans. Then we would have to be specific about his strengths and difficulties, and talk about how his brain just works differently.

Another idea, "The Attributes Activity" from autism guru, Tony Attwood, was to have the whole family present, and to chat about everyone’s strengths and weaknesses, writing them up on charts. After some discussion, we would look at the characteristics of the child with Autism and tell him/her that his characteristics were part of a condition known as Autism (specifying High Functioning/Asperger's or whatever it may be). Attwood suggests being very positive, saying “Congratulations! You have Aspergers”. This approach is one we may explore in the future, however, given the limited attention span of our family members at the dinner table, we decided against it in the short-term.

Then I came across the most beautiful books, “All Cats Have Asperger Syndrome” and “Inside Asperger’s Looking Out” by Kathy Hoopmann. These books combine photographs and text to bring to light many of the unique characteristics of those with Asperger’s. Perhaps these would be the tool we could use to begin to unwrap things with our son? But alas, he found them on my bed one day, read them, then just got up and went on with life as usual, having not been able to make the connection between the books and his own life experiences.

Eventually, enough homework was done, and the time did come when we believed our son was ready to know more about what made him tick. He seemed to be growing in his awareness of being somehow different to the other children. The professionals helping our boy had expressed the view that if a child sensed that they were quite different before they had an explanation, confusion and depression could result. He was already in a phase of moodiness, and we thought perhaps it was coming from this sense of being somehow different.

In the end, my creative husband had come up with his own way of explaining the condition to our son. This method came from his desire for our son to know that, regardless of any diagnosis, he needn't feel limited in terms of his potential - he could contribute something of value to this world. My husband spent time researching about well known people through history who, it is now believed, had Asperger’s syndrome. Then, every few days, we played “Guess Who?” at the dinner table. The kids became familiar with characters like Mozart, Einstein, Michelangelo, Van Gogh, Newton….and learnt that they had certain characteristics.

The fact that Michelangelo had a special interest in the arts would be no surprise to any of us, or that he gave undivided attention to his masterpieces. But, who would have known that Michelangelo found it difficult to maintain close friendships, didn't like crowds, didn't like to bathe, often slept in his clothes, had trouble showing emotions and was socially awkward? (Arshad 2004). Then there was Einstein: Addicted to Physics, he had trouble processing verbal information, suffered from major temper tantrums and day dreamed in school! (Ioan 2003). Mozart was so sensitive to sound that loud sounds could make him physically ill. He only got excited when talking about music. He would move his hands and feet in a repetitive fashion, and would have sudden mood swings (Ashoori & Jankovic 2007). And these are but a few examples of people from the past who were undoubtedly different to those around them.

Yet these people had given the world wonderful gifts in science and the arts. Perhaps life would have been easier for them, if there had have been such a thing as early intervention, which may have helped with their difficulties in their social and sensory worlds. This is what we wanted to eventually convey to our son - that these people didn't even know about the condition they had, and that these days their lives would probably look quite different – still with the same talents, but with more skills to use in their social lives, and with more of an ability to manage their emotions and sensory issues.

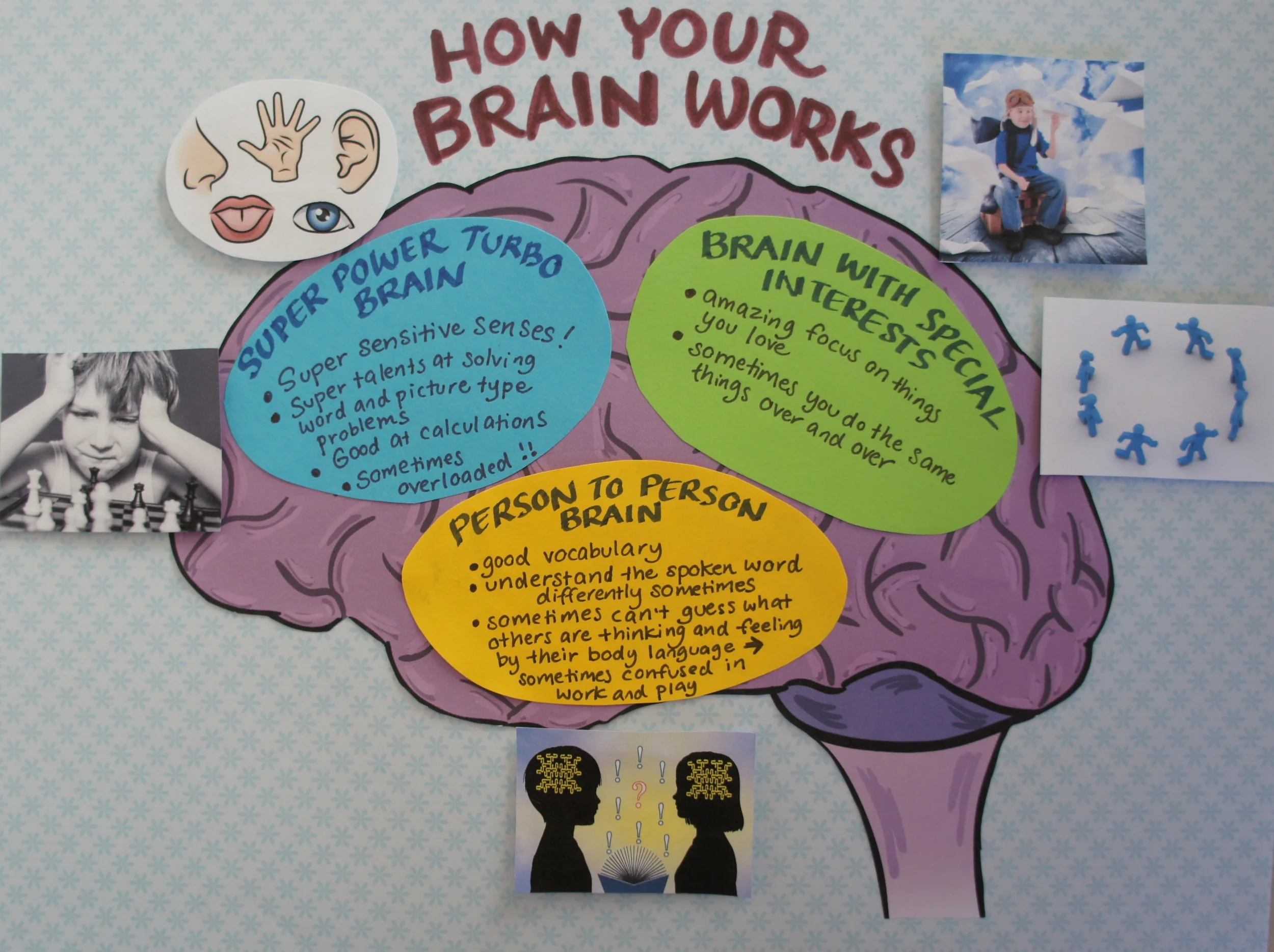

Getting back to our game of ‘Guess Who?”, our family played it for a few weeks. Eventually, it was time for my husband to have a relaxed one to one chat on the bed with our son about these great personalities from the past. He talked about how these people had super power turbo brains, super brains that worked differently to other people’s brains. They were brains that often gave them very good senses – like taste, hearing, smell and sight. They were brains that gave them the ability to focus amazingly well on things they loved, and sometimes even made them want to do the same things over and over again. Yet their super brains could make it hard for them because they took in too much information from outside – it meant they had trouble with noisy, crowded environments and liked to be alone a lot. Their brains, explained my husband, didn’t take in information from the outside world in the same way as other people, and they had trouble working out what other people were thinking and feeling.

Finally, my husband told our son that he too had a super power turbo brain. Using a visual diagram of the brain (see below), and talking specifically about our son and how his brain worked, he told him that he had an Aspergers type brain like the famous people they had been talking about.

How did our son react? After our long journey to get to this point as parents, our son was actually quite indifferent to this disclosure, and said that he didn’t think his brain was so different. Then, that was it. Life as usual. To be honest, it was a bit disappointing that he had not embraced the information we had given him. Maybe we had the timing wrong? Maybe we had forgotten that it takes TIME for a child on the Autistic Spectrum to process information!

In the end, we realised that the gift we had given him was not one that would be fully unwrapped and explored in that moment. In fact, he is still opening it. A diagnosis is something to be processed over a long period of time. We also realised that there were limitations to our approach of sharing genius type personalities from the past, since the child may think they are going to be the next Michelangelo, or feel pressure to become someone just as great! However, our imperfect attempt did not matter, since we had discovered that sharing a diagnosis is a multi-step process, and a continuous one. It wasn't something to be done in one sitting. There was more to come.

We are still giving our son that carefully chosen gift - the gift of knowledge about himself - and he is still taking off the wrapping!

REFERENCES:

Arshad, M. Journal of Medical Biography, June 2004: vol 12, pp.115-120.

Ioan, J 2003, ' Singular Scientists', JR Soc Med, vol 96, no. 1, pp.54-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC539373/

Ashoori, A & Jankovic, J 2007, 'Mozart's Movements and behaviour: a case of Tourette's syndrome?', J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, vol 78,no. 11, pp. 1171-1175. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2117611/

A VISUAL WAY OF EXPLAINING A DIAGNOSIS

We created this diagram to explain to our son how his brain works (every child on the Spectrum is unique, of course, so this is very personal)

Top Resources:

A most informative article giving the basics on telling your child about a diagnosis:

http://autismdigest.com/explaining-the-diagnosis-to-the-child-with-autism/

Tony Attwood's Method of Sharing a Diagnosis

http://www.ahany.org/ShouldYouExplainTheDiagnosis.htm

YouTube video by Dr. Stephen Shore which presents his step by step guide to revealing the diagnosis to your child:

http://www.autismsupportnetwork.com/news/video-when-how-should-you-tell-your-child-about-hisher-autism-diagnosis-37449344 (copy and past this into your browser)

I am Special

A workbook developed by Peter Vermeulen, which is helpful for children from about ten years old, especially in that its content and layout are devised especially for children who read, think and process information differently.

“Inside Asperger’s Looking Out” by Kathy Hoopmann.

This book combines photographs and text to bring to light many of the unique characteristics of those with Asperger’s.